Pedals in a car – what is their layout and how do the clutch, brake and gas work?

A car's pedals are the driver's primary interface with the vehicle—driving would be impossible without them. Their proper operation is crucial for safety and comfort: from the clutch-brake-accelerator sequence in manual cars to the two pedals in automatic cars. In this guide, we explain the pedal layout in a car, the operating principles of each pedal, and provide practical tips for using the pedals consciously and smoothly—regardless of transmission type.

How are the pedals positioned in a car? – A standard that saves lives

Universal pedal system for vehicles with manual transmission

In manual cars, the pedal layout (from left to right) is fixed: clutch – brake – accelerator. This is a global standard that minimizes the risk of confusion and facilitates adaptation between different models. Importantly, in right-hand drive cars (left-hand drive), the order remains identical – left→right: clutch, brake, accelerator – only the driver's position changes.

The foot assignment is also consistent: the left foot operates solely the clutch, the right foot alternates between the brake and gas pedals (always one pedal at a time). This creates a safe reflex: if you need to decelerate suddenly, the right foot has priority on the brake. Furthermore, the brake is positioned slightly higher and has less free play than the gas pedal, preventing accidental acceleration.

Why is this setting so important?

- builds consistent muscle memory in drivers,

- reduces the risk of pressing the wrong pedal under stress,

- allows for a smooth transition from brake to gas and vice versa without "searching" for the pedals.

Pedal system in cars with automatic transmission

Automatic cars have a simplified layout: there's no clutch pedal. The car has two pedals: the left brake (often wider) and the right gas pedal. Both pedals are operated solely by the right foot. The left foot rests on the footrest – a key safety habit, as using the left foot for braking increases the risk of accidental double-pedaling and slower reaction times.

In practice:

- right foot – gas ↔ brake (alternately),

- left foot – resting on the footrest.

This split ensures consistency with manuals (the right foot still controls the brake) and shortens the path to a safe response. It's also the foundation of smooth driving: it's easier to apply the gas and brake without both feet fighting for the same range of motion.

Clutch operation – how to use it skillfully?

The function of the clutch in the drive system

The clutch is the "link" between the engine and the gearbox. It allows for momentary disengagement and smooth re-engagement of the drive, allowing you to safely change gears and move off. In its simplest form, the clutch assembly consists of a clutch disc (with friction linings), a pressure plate (a diaphragm spring that presses the disc against the flywheel), and a release bearing (facilitates disengagement). When you press the pedal, the pressure plate moves the disc away from the flywheel, disengaging the drive. When you release the pedal, the disc "catches" again and transfers torque to the gearbox. In practice, the "clutch, brake, gas" sequence in manual vehicles makes maneuvers predictable and safe—this is the foundation upon which pedal operation in a car is based.

Skillful use of the clutch pedal – rules for smooth driving

The key is precise control of the gear shift and smooth left foot movement. Depress the clutch fully, quickly and decisively – only fully disengaging the clutch prevents grinding of the synchronizers. Release it gradually, especially when starting: first gently to the "catch point," and only then fully, in sync with a light application of the accelerator. Avoid "riding the clutch" – keeping your foot on the pedal or half-pressing the clutch while driving causes overheating and excessive friction wear. When changing gears, follow this pattern: release the accelerator → fully depress the clutch → change gear → smoothly release the clutch + return to the accelerator. In traffic, it's better to use first gear and coast calmly than to maintain traffic on a half-clutch.

Practical tips:

- When starting on a hill, use the parking brake or hill hold assist instead of holding the revs with the half-clutch.

- Don't over-accelerate – a slight addition of gas is enough (especially in modern engines with torque from low revs).

- Once you have changed gear and fully engaged the clutch, remove your left foot from the pedal and place it on the footrest.

Clutch wear signs – what to look out for?

A worn clutch presents clear symptoms. The most characteristic symptom is slipping: the engine revs up, but the car doesn't accelerate adequately, especially in higher gears. Common signs include jerking when starting, difficult or noisy gear changes, and a burning smell after a failed uphill start. The clutch engagement point can also shift very high or very low. If you notice any of these pedal behaviors in your car, schedule a diagnostic – early intervention usually reduces costs (e.g., replacing just the disc instead of the entire assembly including the dual-mass flywheel).

Car brakes – what is worth knowing?

The mechanism of operation of the braking system

A car's brakes operate thanks to a hydraulic system. When you press the pedal, the force of your foot is transferred to the master cylinder, which increases the brake fluid pressure in the lines. This pressure compresses the caliper pistons against the pads, and the pads against the discs (or the shoes against the drums), converting kinetic energy into heat and reducing speed. Key elements include: efficient fluid (hygroscopic – requires periodic replacement), tight lines, well-functioning calipers, and pads and discs of the appropriate thickness. The system is coordinated with the ABS (anti-lock braking system, maintaining steering control) and ESP (stabilizing the driving path by applying braking to selected wheels). This means that regardless of where the brake is in the car – always under your right foot – the response is quick and predictable in critical situations.

Correct use of the brake – techniques and safety

Effective braking is all about smoothness and progression. Start gently, then gradually increase pressure to shift the car's weight forward and improve front-wheel traction. In an emergency, use emergency braking: in cars with ABS, press the pedal firmly, all the way down, maintaining your directional position; pedal pulsation and vibration are normal signs of the system's operation. On long descents, support the discs with engine braking – downshifting increases engine resistance, reducing the load on the brake pads and reducing overheating. Remember that in the clutch-brake-accelerator configuration, the brake is the most frequently used pedal, and you always operate it with your right foot (even in automatic transmissions), which shortens reaction time and prevents accidental accelerator application.

Good habits:

- Maintain an appropriate distance to brake earlier and more gently.

- Look far ahead – this will give you time to brake progressively instead of suddenly.

- After heavy braking, do not keep your foot on the pedal unnecessarily (you will heat the discs unnecessarily).

Brake problems – when to seek help?

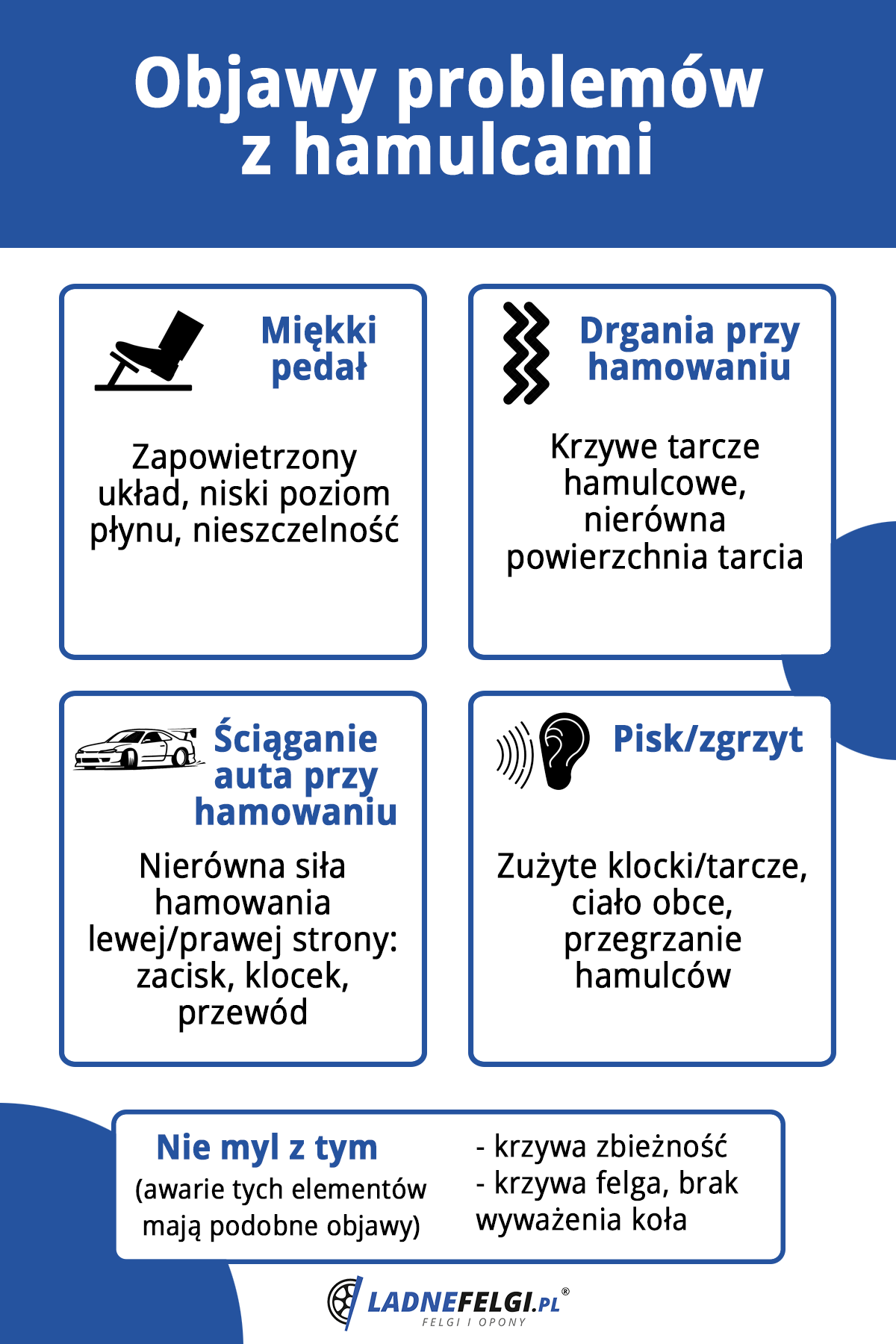

The braking system should operate consistently and without surprises. Warning signals include:

- Soft pedal or extended travel – possible air lock, fluid loss, leak.

- A “thumping” sound on the pedal/steering wheel – often a symptom of warped discs or uneven friction.

- Car pulling when braking – differences in braking force on both sides (caliper, pad, hose).

- Squeaks, grinding, metallic sound – worn pads/discs, foreign bodies, overheating.

Each of these symptoms requires immediate diagnosis – this isn't something you can "drive with." Regular inspections (checking pad thickness, disc condition, fluid level and quality) and proper driving habits will ensure your car's brakes remain your most reliable safety ally.

Gas – the most important pedal in the car

Gas pedal function – engine power control

The accelerator pedal regulates the amount of air and fuel entering the engine, and therefore its RPM and torque/power. In older cars, the signal from the pedal traveled via a cable to the carburetor/injection throttle body; today, almost everywhere, electronic throttle control (drive-by-wire) operates: a pedal position sensor sends a signal to the ECU, which precisely adjusts the throttle opening and fuel delivery (and, in turbocharged engines, boost pressure as well). This ensures smooth response, and safety systems (ASR/ESP) can intelligently "request" less power from the engine when the wheels lose traction—without driver intervention.

Skillful gas management – economics and dynamics

The right foot dictates driving style. Smooth, predictable pedal movements improve comfort and reduce fuel consumption.

- Accelerate smoothly. Instead of flooring the accelerator, increase the pressure gradually—the engine will enter its efficient range more quickly and won't overflow fuel.

- Optimal RPM. Keep the engine in the range where it's most efficient (usually mid-range RPM; lower for diesels, slightly higher for petrols). Avoid both "tiring" at very low RPMs and "revving" at high RPMs unnecessarily for extended periods.

- Ecodriving. Look far ahead, release the gas pedal early (decelerating in gear/coasting), maintain a constant speed, and use cruise control. Gentle throttle operation is less tiring for passengers and the drivetrain, and reduces tire wear.

Potential problems with the gas pedal

Although rare, situations do occur that require an immediate driver response.

- Sticking pedal/carpet wiper. If the accelerator pedal doesn't respond or the carpet is jammed against the pedal, depress the brake firmly, shift to neutral (N) in manual/automatic transmission, and pull over safely; turn off the engine only after coming to a complete stop.

- Electronic faults (drive-by-wire). Symptoms: delayed response, "limp mode," rough acceleration. Solution: diagnostics (pedal position sensor, throttle body, wiring harness, ECU).

- Dirty throttle body. RPM spikes and jerking under gentle throttle input may indicate contamination—cleaning and adjusting the throttle body can help.

If you notice an unusually hard/soft pedal travel, revs "holding," or spontaneous acceleration, remain calm and respond with the emergency procedure described above. Smooth throttle and proper right foot habits are just as important to safety as proper brake and clutch use.

Hybrid and electric cars – what are the differences between pedal operation?

Modern hybrid (HEV, PHEV) and electric (EV) cars still have the same basic pedals for the driver: gas (accelerator) and brake. There's no clutch pedal. But the way these pedals "behave" and what they actually do in the drivetrain is slightly different than in a typical combustion car. And you can feel it underfoot.

Hybrid/electric brake: first energy recovery, then pad and disc

In a combustion car, you press the brake → brake fluid increases pressure → the pad presses against the disc → the car slows down by friction (converting speed into heat).

In hybrid and electric cars, this works in two stages:

1. Regenerative braking

- Instead of using the blocks directly, the car uses the electric motor as a generator.

- The wheels drive the motor, the motor creates resistance and at the same time produces electricity that charges the battery.

- The driver feels this as a "soft, smooth" deceleration when the brake is pressed lightly.

- The result: you wear out your pads and discs less, and some of the braking energy is returned to the battery.

2. Mechanical braking (discs/pads/drums)

- If you press the pedal harder, or the battery can no longer accept any more energy (e.g. it is almost full), the computer smoothly engages the classic friction brakes.

- It's the same as in a combustion engine car: piston, pad, disc.

Important for the driver:

- Braking force can be more linear at low pressure and then increase significantly with higher pressure. Initially, it's mainly regenerative braking, then the conventional brake kicks in.

- Sometimes this makes the brake feel like it's "behaving differently than in my old car," especially when pressed very gently. This doesn't mean the brake is faulty—it means the car is recuperating energy instead of wasting it.

- On long mountain descents, regenerative braking helps keep the discs cool, so the brakes don't overheat. However, as the battery fills up, the car switches more to mechanical braking. The pedal can then begin to feel more "normal," like a combustion engine.

This is a big difference in experience: the brake pedal in a hybrid/electric car does not always have "one constant" behavior throughout the entire journey, because the share of recuperation changes.

Driving with "one pedal" in electric cars

Many electric cars feature a powerful recuperation mode. In practice:

- You take your foot off the gas → the car starts to slow down on its own, as if you were braking slightly.

- In the city, you often don't have to touch the brake pedal until you come to a stop - you can practically drive solely on the gas pedal.

What does this change for the driver?

- The gas pedal is no longer "I just accelerate", it becomes "I regulate the speed in both directions": I press = faster, I release = slow down.

- This gives a very smooth ride in traffic jams and uses less brake wear.

- If someone is driving an electric car for the first time, they might get the impression that the car "brakes itself when I let off the gas." This is normal, not a malfunction.

The accelerator pedal in hybrids and electric cars: immediate response

In a classic combustion car:

- you press the gas → the throttle valve lets in air → the engine revs up → the gearbox responds → you only feel the acceleration.

- In turbo petrol/diesel engines there is so-called turbo lag: a delay before the turbo kicks in.

In an electric car:

- you press the gas → the electric motor immediately provides torque

- the response is immediate, even brutally fast when pressed harder.

- The result: the car can "jump forward" even with light throttle, especially on wet asphalt or snow.

In hybrid:

- The computer decides whether to use the electric motor, the combustion engine, or both.

- Therefore, the driver may feel that the car responds "electrically and softly" at times, and then "with the roar of an internal combustion engine." This is normal hybrid operation – the revs don't fluctuate.

Why is this important practically?

- On slippery surfaces (snow, ice, wet leaves), suddenly accelerating in an electric car or a powerful hybrid can easily break the traction of the driven wheels because the torque is available immediately.

- This means that the gas pedal in an EV requires a more gentle foot pressure when starting in winter than in a regular naturally aspirated car.

Clutch (or rather: lack thereof)

- In most hybrids and all electric cars, the driver does not have a clutch pedal.

- Starting and changing gears are computer-controlled (planetary gear, single-speed gearbox or automatically controlled multi-clutch gearbox).

- There is no need to "catch the clutch point", there is no risk of burning out the clutch when starting uphill.

- This also means less stress for the novice driver.

An electric car doesn't have a traditional clutch, but it can still have drivetrain components that perform a similar function (multi-plate clutches in hybrids, a torque converter in automatics, etc.). The difference is that the driver doesn't operate them.

Modern design

Modern design Perfect fit

Perfect fit High durability

High durability Free shipping within 24 hours

Free shipping within 24 hours

Individual project

Individual project Dedicated caregiver

Dedicated caregiver